The most expensive education program in human history

Or: How the West paid $275 billion to create the new Chinese industrial ecosystem

Welcome to my notes. I dig into things until they make sense, then I write it down so I don’t forget and you don’t have to do the work. Sometimes I’m wrong. Sometimes I’m not. Either way, it’s going to be interesting.

Subscribe and let’s learn together.

Hey there! 👋

Skander here.

Let me tell you about the most expensive education program in human history.

It wasn’t a university. It wasn’t a government training initiative. It was a company you’ve heard of: Apple.

In 1996, Apple was weeks from bankruptcy. They were bleeding cash, losing market share, and producing in the US, which was expensive. Something had to change.

Over the next two decades, Apple built the most sophisticated manufacturing partnership the world had ever seen. They moved production from the US to Singapore to Taiwan to Korea and finally, massively, to China. Their primary partner: a Taiwanese company called Foxconn that had set up shop in Shenzhen.

Here are the numbers and my favorite fun fact:

$275 billion invested in the Chinese economy

28 million workers trained to Apple’s manufacturing standards

An entire city (literally called “iPhone City”) built around Apple’s production needs

When reports surfaced about poor working conditions at Foxconn, Apple commissioned a study to defend itself. The study’s findings accidentally revealed the scale of what they’d created: Apple had invested more in Chinese manufacturing capability than the Marshall Plan invested in rebuilding post-war Europe.

The Marshall Plan, adjusted for inflation, was around $150 billion. Apple beat it by almost 2x.

And this is not the only time this happened.

🌊 Let’s dive in

I recently sat down with my friend Andreas Klinger on his YouTube channel PROTOTYPE to talk about this. What follows is an adapted version of that conversation.

If you prefer video with more case studies, better jokes and more human, here it is 👇

Okay, let’s get to the case study: Apple didn’t just send money and machines. They sent teachers.

When Foxconn needed to scale up iPhone production in 2007, Apple looked at how long it would take to recruit 8,000-9,000 industrial engineers from the US and train them to Apple standards. Answer: about 9 months.

Foxconn did it in 15 days.

How? They recruited locally, brought in the bodies, and then Apple flew over their best engineers, MIT and Stanford grads who had been developing the iPhone prototypes, to train the Chinese workforce on Apple’s processes.

Think about that. Apple sent the people who invented the thing to teach others how to make it. They didn’t just export production. They exported the accumulated knowledge of their most talented engineers.

And Foxconn wasn’t stupid. They treated Apple like a university. Workers would get trained on Apple lines for 6-12 months, then get rotated to other clients (Samsung, Xiaomi, whoever) bringing their newly acquired Apple-grade skills with them. Then Foxconn would bring in fresh workers for Apple to train all over again.

The Smile Curve is a Trap

It was a knowledge transfer operation, and Apple was paying for it.

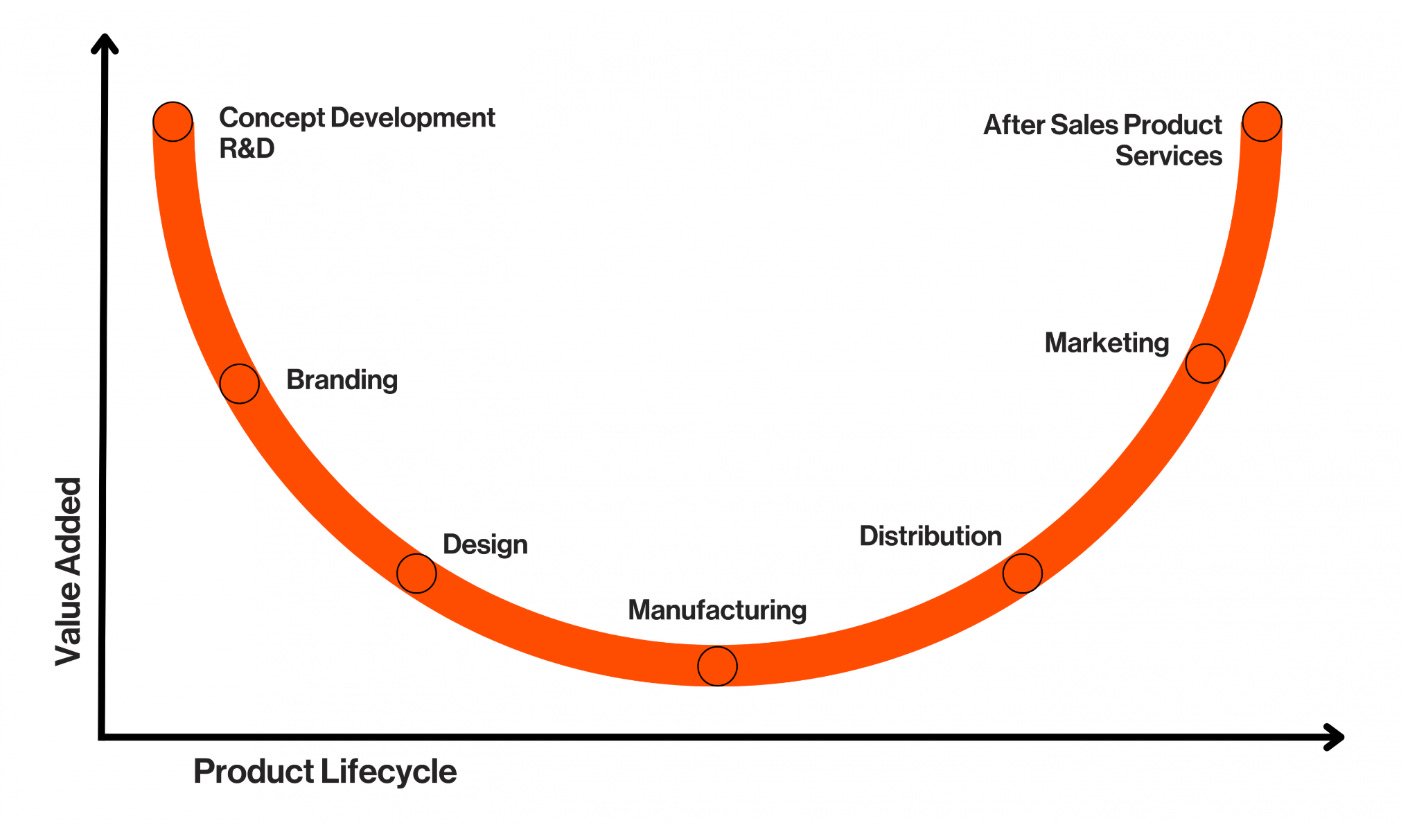

In 1992, a Taiwanese businessman named Stan Shih drew a curve on a whiteboard.

The curve looked like a smile. On the left side: R&D and design. High value. On the right side: marketing and brand. High value. In the middle, at the bottom of the smile: manufacturing.

Low value. Commodity work. Anyone can do it.

The message was elegant and persuasive: Don’t waste your time on the boring middle. Focus on what matters: the ideas and the brand. Let someone else do the assembly.

Western executives loved this framework. It validated everything they wanted to believe. Manufacturing was sweaty work. It was low-margin. It was, frankly, kind of gross. The real alpha was in thinking.

So they outsourced. They outsourced everything. First to Taiwan. Then to China. They kept the “valuable” stuff: the patents, the designs, the logos. And shipped the grunt work overseas.

Here’s the punchline: Stan Shih was the CEO of Acer.

Yes, that Acer. The company that started as a contract manufacturer, used the smile curve pitch to convince Western companies to give them their manufacturing, and then (once they’d accumulated enough knowledge) launched their own consumer brand and ate their customers’ lunch.

The smile curve wasn’t an observation. It was a strategy. And the strategy wasn’t for the companies being pitched. It was for Shih’s own company.

The Gravity Well

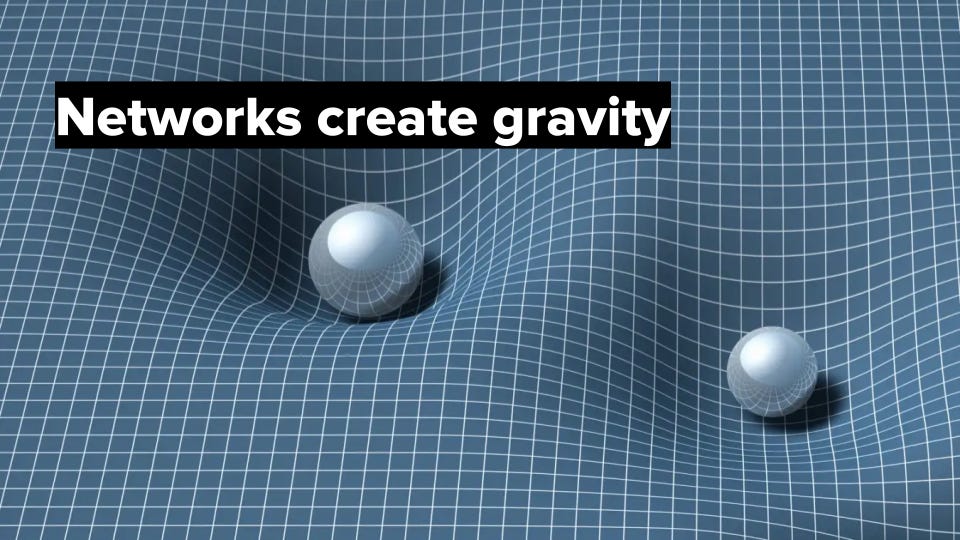

Supply chains aren’t just lists of suppliers. They’re ecosystems. And ecosystems have gravity.

Once enough manufacturing concentrates in one place, it starts pulling in everything else. Suppliers want to be near their customers. Customers want to be near their suppliers. Engineers want to be where the action is.

Consider Corning, the company that makes the Gorilla Glass on your phone screen.

Corning is an American company, founded in 1851, headquartered in New York. For most of its history, it made glass in America. But then it ran into a problem.

Here’s a quote from their CFO, James Flaws: they found that all their customers (not just Apple, but Samsung, LG, everyone) were now manufacturing in Asia. They could make the glass in America, sure. But then they’d have to ship it across the Pacific, which took 35 days by boat.

Thirty-five days. In an industry where phone models change every 12 months.

They could air freight it, but that was prohibitively expensive for heavy glass panels.

So what did Corning do?

They moved their glass factories to China. An American company, with American IP, building American-invented products... in China. Because the assembly was in China, and you can’t have a 35-day supply chain when your competitors have a same-day one.

Supply chains create gravity wells. Once enough mass accumulates, everything else falls toward it.

This is the part the smile curve doesn’t show you. The curve makes it look like R&D and manufacturing are independent activities. They’re not. They’re deeply entangled. The more manufacturing you do, the more you learn. The more you learn, the better your R&D gets. Ship the manufacturing overseas and you don’t just lose the grunt work. You lose the learning. You lose the gravity.

Dell’s Excellent Adventure

Before Apple, there was Dell.

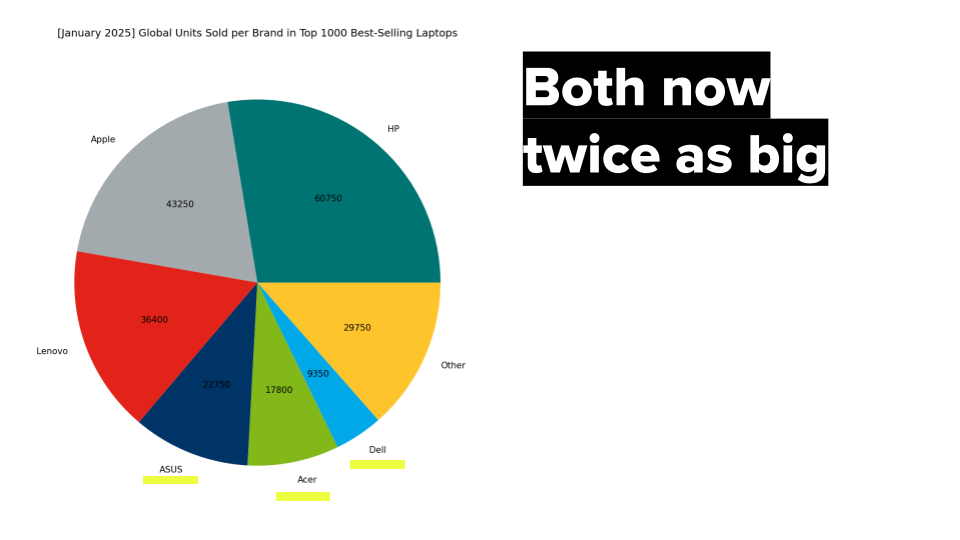

In the 1990s, Dell was the king of PCs. Their “Dell Direct” model was a case study in business school efficiency: configure online, ship from factory, no inventory, no retail markup.

But Dell looked at the smile curve and saw opportunity. Manufacturing PCs was low-margin, commoditized work. Why keep it in-house when you could outsource it and focus on what matters: brand, distribution, customer relationships?

So they found suppliers. Lots of suppliers. They outsourced circuit boards, motherboards, assembly. Eventually they outsourced design too. What was left was basically the Dell logo and the website.

Meanwhile, their suppliers were getting better. Getting smarter. Accumulating process knowledge.

In 2005, one of those suppliers launched its own consumer laptop brand.

That supplier’s name was Asus.

Shortly after, another supplier did the same thing.

That supplier’s name was Acer. (Yes, the smile curve guy.)

Today, both Asus and Acer are now selling more laptops than Dell.

Let that sink in. Dell’s suppliers became Dell’s competitors, and then Dell’s superiors. The companies Dell was paying to do the “low-value” work climbed the value chain, learned everything they needed to know, and launched their own brands.

This is what happens when you confuse margin with value. Manufacturing had low margins, so Dell assumed it had low value. But value and margin aren’t the same thing. Manufacturing was where the learning happened. By outsourcing the learning, Dell outsourced their future.

The Catfish Effect

Let’s talk about Tesla, because it’s the counterexample that proves the rule.

For decades, China tried to build a domestic auto industry through joint ventures. The playbook: partner with Western automakers, require technology transfer, build local capability. The goal, explicitly stated, was “the first machine is imported, the second machine is made in China, the third machine is exported.”

It didn’t work.

Thirty years of joint ventures, and China still couldn’t make a globally competitive car. Their domestic brands were weak. The supply chain was mediocre. Something was missing.

Then, in 2019, Tesla showed up.

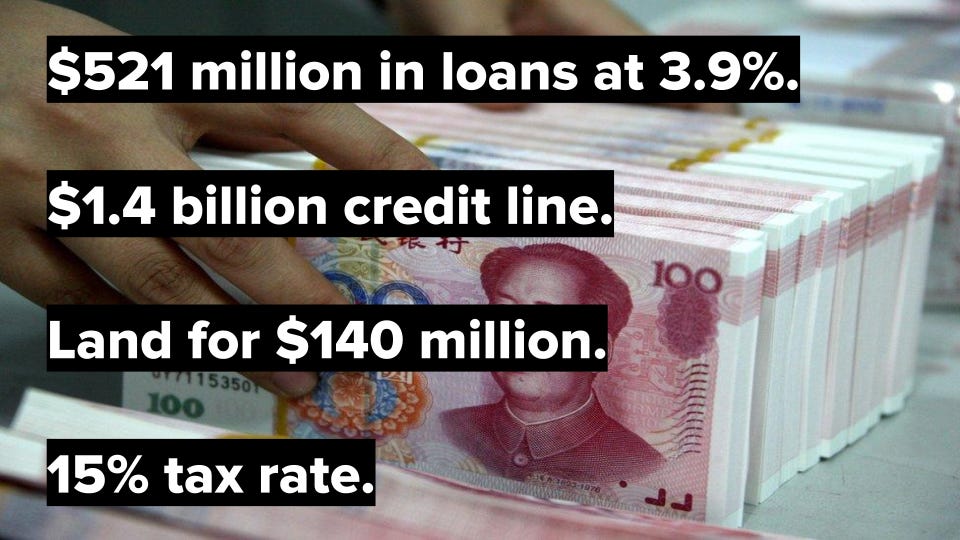

China rolled out the red carpet like no one has ever rolled out a red carpet. They gave Tesla something no foreign automaker had ever received: permission to build a wholly-owned factory, no joint venture required. They threw in billions in loans, cheap land, and a tax rate so low it was basically zero.

And then Tesla did something remarkable. They built a factory from dirt to production cars in under 12 months.

When Musk first announced the Shanghai Gigafactory, industry observers expected it would take 2+ years to get running. The factory broke ground in January 2019. The first cars rolled off the line in December 2019. Eleven months.

But here’s the twist: the Chinese government wasn’t just trying to help Tesla. They were using Tesla as a catfish.

The catfish effect.

The story goes like this: when you’re transporting sardines in a tank, they get lazy. They float around, barely moving, and by the time they arrive, they’re sluggish and not very tasty. But if you drop a catfish in the tank—a natural predator—suddenly everyone starts swimming. Competition makes the sardines better.

Tesla was the catfish.

By bringing in the most advanced EV manufacturer in the world, China forced its domestic companies to level up. BYD, Nio, Xpeng. They had to compete with Tesla, on their home turf, with Tesla operating at full strength.

More importantly, Tesla brought its entire supplier ecosystem with them. Companies like LK Group, which had made plastic toys and small die-cast parts, suddenly found themselves working with Tesla to develop Giga Casting: massive single-piece aluminum body parts that revolutionized car manufacturing.

LK Group developed this technology with Tesla. And then they sold those same machines to Tesla’s Chinese competitors.

The catfish didn’t just make the sardines swim faster. The catfish taught the sardines how to be catfish.

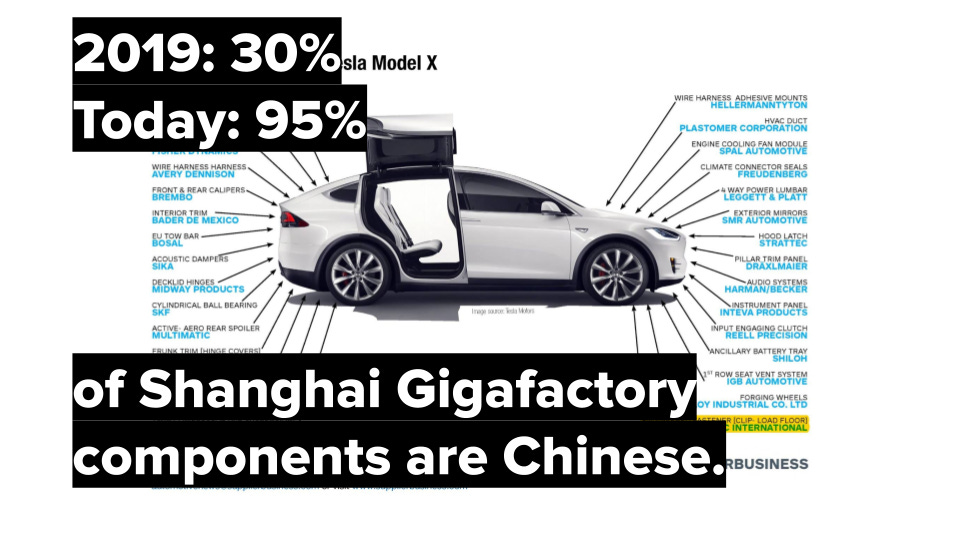

Today, Tesla’s Shanghai factory runs on 95% Chinese components. When it opened, it was mostly foreign parts just assembled in China. Now it’s essentially a Chinese supply chain making a car with a Tesla logo on it.

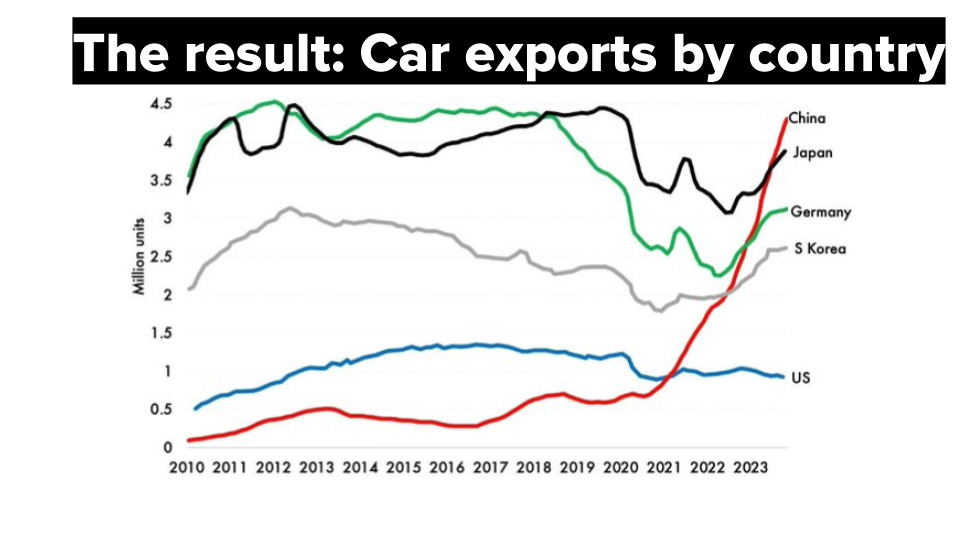

And here’s the punchline: China’s car exports went from basically nothing to the largest in the world. In 2019, before the Tesla factory, Chinese automakers were barely a rounding error in global exports. By 2024, China was the #1 car exporter on Earth.

Thirty years of joint ventures failed. Three years with Tesla succeeded.

The difference? Tesla didn’t just come to make cars. They came to build a supplier ecosystem. And once that ecosystem existed, it served everyone.

Pharma’s Foxconn

So is this pattern limited to tech and cars? Nope.

Let me introduce you to WuXi AppTec, the Foxconn of pharmaceuticals.

WuXi was founded in 2000. Today, they work with 6,000+ partners in 30+ countries. They’re fully FDA compliant. And they don’t just do the “low-value” manufacturing work.

They do R&D.

See, Western pharma companies looked at the smile curve and made the same mistake everyone else did. The valuable part is the research, right? The molecule design, the clinical trials, the patents. Manufacturing is just pills in bottles. Anyone can do that.

So they outsourced manufacturing. Then, to cut costs further, they outsourced some research. WuXi was happy to help. They could do trials cheaper, faster, less regulatory friction. It was a win-win.

Here’s what that win-win looks like today:

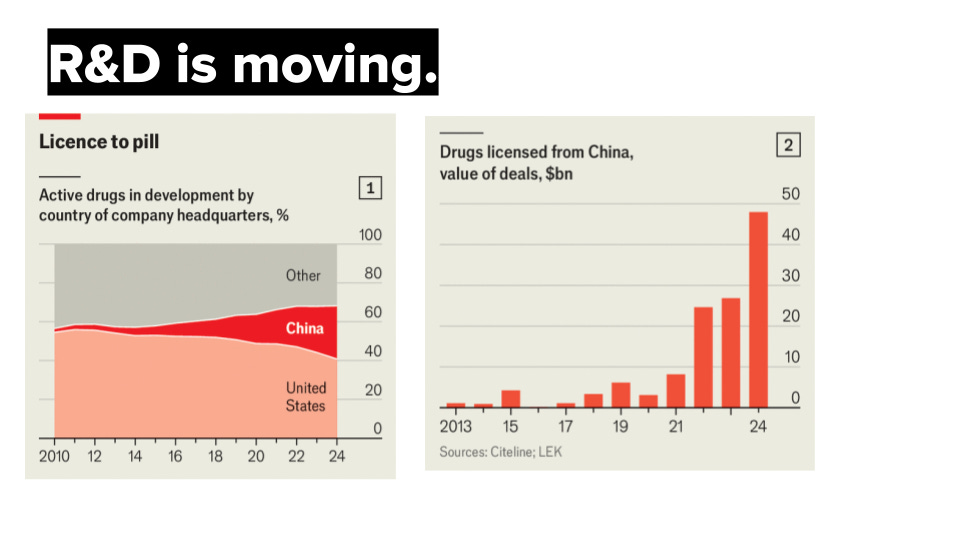

In 2010, Chinese companies had a tiny fraction of drugs in development globally

Today, 20% of all drugs in development worldwide are being developed in China

Last year alone, Chinese companies licensed $50 billion worth of new drug patents to Western pharma

The pill-bottle people are now the molecule-design people. The “low-value” manufacturers climbed the smile curve on both sides.

And unlike tech or cars, where at least you can see what’s happening, pharma is invisible. You buy ibuprofen at CVS and you have no idea that 90% of global ibuprofen is manufactured in China. You take a generic prescription and you don’t know that even if it’s “made in India,” the active pharmaceutical ingredients probably came from Chinese chemical plants.

We are literally paying China to develop the drugs we’ll need in the future. We’re paying tuition (again) for another $275 billion education program.

Except this time the stakes aren’t smartphones. They’re medicine.

The Trap, Revealed

Okay. Let me tie this all together.

The smile curve was a trap. But it wasn’t a trap because it was wrong. The curve is technically accurate: manufacturing does have lower margins than R&D and brand.

The trap is that it conflated margin with value.

Manufacturing has low margins. But manufacturing is where the learning happens. It’s where process knowledge accumulates. It’s where you figure out what’s actually possible to make, which feeds back into what’s possible to design.

The smile curve treats the value chain like independent chunks. In reality, it’s a loop. R&D informs manufacturing. Manufacturing informs R&D. Separate them by an ocean and you break the feedback loop.

Here’s what actually happens when you outsource:

Year 1-5: Cost savings! Your margins improve. Wall Street loves you.

Year 5-10: Your manufacturing partners start suggesting design changes. They know more about production than you do now. You listen (it saves money).

Year 10-15: Your “design” is increasingly just picking from options your manufacturers propose. The real innovation is happening on their factory floors.

Year 15-20: Your manufacturers launch competing products. They have the process knowledge, the supply chains, the engineering talent. All you have is a logo and some old patents.

Year 20+: You are a brand licensing company. Maybe a hedge fund that happens to own trademarks.

This is Dell. This is happening to Apple. This is happening across every industry that fell for the smile curve.

Whoever makes it, learns it. Whoever learns it, owns it.

Can Europe Play the Game in Reverse?

Is there anything to be done?

The obvious move is to try China’s playbook in reverse. Invite Chinese manufacturers to build factories in Europe, require technology transfer, develop local supply chains, climb the value curve from the other direction.

It’s actually being tried. Stellantis (the conglomerate that owns Fiat, Peugeot, Maserati, Jeep, Chrysler, basically half the car industry) just announced a 50/50 joint venture with CATL, the Chinese battery giant. They’re building a $4 billion factory in Spain.

But here’s the question nobody wants to ask: Why would China let this work?

China is already trying to make technology transfer a one-way gate. Foxconn workers who were helping build iPhone supply chains in India? Suddenly can’t get visas. Equipment shipments to non-Chinese factories? Mysteriously delayed.

And even if the factories get built: Will it matter? Will European workers learn what they need to learn, or will they just be button-pushers for automated Chinese machines?

There’s a recent headline: Tesla’s Berlin Gigafactory now uses 92% European-sourced components. That’s up from 60% just a few years ago. That’s the trend line you want: Local supply chains developing, local knowledge accumulating.

But Tesla in Berlin isn’t a joint venture with technology transfer requirements. It’s Tesla being Tesla, and Europe being the beneficiary. What happens when the catfish leaves?

The Lesson

Here’s what I want you to take away from this:

Manufacturing is knowledge. Outsourcing is knowledge transfer.

The smile curve convinced a generation of executives that they could keep the valuable parts and ship the rest overseas. They were wrong. The “rest” was where the value was being created all along.

China didn’t steal this. Not mostly, anyway. We gave it to them. We paid them (handsomely) to learn everything we knew. We sent our best engineers to train their workforce. We moved our factories into their gravity well and then wondered why we couldn’t pull them back out.

What Now?

I don’t have a tidy answer. This is genuinely hard.

But a few things seem clear:

Stop falling for the smile curve. If someone tells you manufacturing is “low-value commodity work,” they’re either confused or trying to sell you something.

Understand the gravity. Supply chains are ecosystems. Once they reach critical mass somewhere, pulling them back is extraordinarily hard. You need to build new gravity wells, not just offer subsidies.

Accept that this takes decades. China’s industrial ascent wasn’t 5 years or 10 years. It was 40 years of patient, strategic, grinding work. Reversing it (if it’s even possible) will take similar patience.

Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good. Europe has 92% local components in one Tesla factory. That’s not full reshoring, but it’s something. Build from there.

Get in the reps. There’s no hack. There’s no shortcut. If you want to manufacture, you have to manufacture. If you want process knowledge, you have to do the process. Over and over and over again.

The West spent forty years convincing itself that thinking was more valuable than making. That ideas were more important than execution. That you could keep the brain and export the hands.

We were wrong.

The hands and the brain are connected. Sever the nerve and eventually both wither.

It’s time to reconnect.

Okay, do you want to dive deeper? Start with our Youtube video on this:

There are other people who are thinking hard about this.

I highly recommend Noah’s recent take on the 2nd China Shock and Europe’s potential reactions to it:

And Packy’s mini book on the Electric Slide, our new electric tech stack that China currently owns (thanks to learning curves & outsourcing) and where we are making progress: